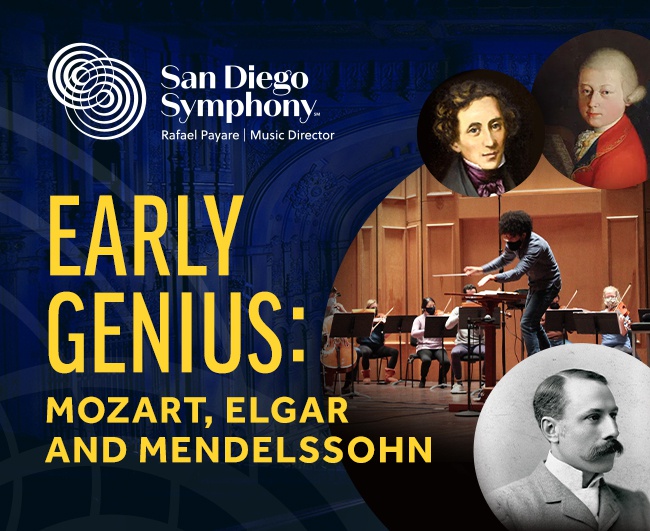

String music of Mozart, Elgar and Mendelssohn

"EARLY GENIUS"

STREAMS FRIDAY, APRIL 30 @ 7PM PDST!

San Diego Symphony musicians shine in a youthful program that captures the intimate yet sweeping power of a string ensemble. Join Music Director Rafael Payare and musicians of the San Diego Symphony on Friday, April 30 at 7pm for "Early Genius: String Music of Mozart, Elgar and Mendelssohn"! The program begins with a work that showcases Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's spirited musical charm when he composed a piece at the mere age of 16: Divertimento in F Major. Edward Elgar's first masterpiece takes center stage for the strings to sing in the sweeping Serenade for Strings. Another young prodigy, Felix Mendelssohn, studied the music of Bach and Mozart while writing 13 symphonies between the ages of 12 and 14. The program closes with Mendelssohn's String Symphony No. 12, a work that captures the influence of these masters with chromatic tension and fugues that create powerful dialogues between the string sections.

San Diego Symphony Orchestra

Rafael Payare, conductor

COMPLETE PROGRAM:

MOZART: Divertimento in F Major, K. 138

ELGAR: Serenade for Strings in E minor, Op. 20

MENDELSSOHN: String Symphony No. 12 in G minor

PROGRAM NOTES:

Divertimento in F Major, K. 138

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-91)

Mozart wrote three “divertimenti” for strings in Salzburg in 1772, when he was 16, but a certain amount of mystery continues to surround this music. The designation “Divertimenti” in the manuscript is not in Mozart’s hand, and these three pieces lack the minuet movements characteristic of the divertimento form. Even the size of the instrumental forces Mozart had in mind is unclear: though scored for four string instruments, these works may be played by either quartet or string orchestra.

Mozart biographer Alfred Einstein has suggested that these three pieces, composed after Mozart’s second trip to Italy, may have been written for use during his third Italian tour late in 1772 and that the simple addition of horns and oboes would transform these quartet-like works into symphonies on the three-movement Italian model. And so Mozart may have extracted double service from these three pieces: as divertimentos for string quartet in Salzburg and as potential symphonies for the court of Milan. The uncertainty about the form of these works has led to their being classified variously (and erroneously) as the “Salzburg symphonies” and “quartet-symphonies.”

The last of the three, Divertimento in F Major, K.138, is a jewel: a fully-formed string symphony only nine minutes long. The sonata-form opening movement (Mozart left no tempo indication, but it is clearly some form of Allegro) opens with a two-part theme – the powerful opening figure and its soft “answer” – followed by a flowing main idea announced and decorated by the two violin sections. This is followed by a genuinely moving Andante, in which the sixteen-year-old composer offers music whose haunting lyric lines foreshadow the great slow movements of his final years. The Presto is a sparkling rondo, complete with two contrasting episodes – the chirping second a pure delight – and a coda. This polished finale sizzles past in one hundred seconds.

Serenade for Strings in E minor, Op. 20

SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857-1934)

Elgar made his way slowly as a composer. He supported himself as a young man by playing the violin in orchestras, giving lessons, conducting and trying to compose. It was a long and difficult apprenticeship: he composed the Serenade for Strings – which biographer Michael Kennedy calls “Elgar’s first masterpiece” – in 1892, when he was 35, the age at which Mozart died.

The brief Serenade for Strings remains the most frequently performed of Elgar’s early compositions. It is full of pleasing themes, and the graceful writing for strings reflects Elgar’s training as a violinist. The character of the entire work is suggested by the composer’s marking for the first movement, Allegro piacevole. Piacevole means “agreeable,” and the Serenade is most agreeable music throughout its twelve-minute span. The opening movement is in ABA form. Over the violas’ dotted rhythm, violins sound the rising-and-falling main idea. Here and throughout the Serenade, the themes do not really develop – Elgar’s method is simply to repeat his themes, but in different registers, dynamics and colors. The arching introduction of the Larghetto leads to this movement’s only theme, a noble melody announced by violins and marked dolce. This repeats, growing more impassioned with each repetition, before the movement dies away to end very quietly – Elgar mutes the strings in the final measures. The finale flows along the easy swing of its 12/8 meter. At the close, Elgar brings back the dotted rhythm and theme from the first movement, and on this music the Serenade rises gently to the quiet concluding chord.

String Symphony No. 12 in G minor

FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809-47)

Mendelssohn was a prodigy whose gifts rivaled, perhaps even surpassed, those of the young Mozart, and he was born into exactly the right family for a young composer. His parents recognized the boy’s talent early and brought in one of the finest pedagogues in Europe, Carl Zelter, as his private tutor. The parents also hired professional musicians for the family’s regular Sunday afternoon musicales in their Berlin home, and so young Felix could hear his compositions performed by the finest musicians available, often when the ink was still wet on his manuscripts. The boy made the most of these opportunities: he learned to conduct very early, and a remarkable drawing survives showing the tiny boy standing on a chair in the family music room as he leads an ensemble of professional musicians.

As part of his instruction, Zelter asked young Mendelssohn to compose a series of symphonies for string orchestra, using the music of Mozart and Bach as his models, and Mendelssohn composed thirteen string symphonies during the years 1821-23 (when he was between the ages of 12 and 14). These symphonies, part of the vast number of apprentice works that Mendelssohn wrote as a boy, were doubtless performed at the Sunday afternoon musicales but were never intended for publication and remained in manuscript for well over a century after the composer’s death. Discovered and published in the years after World War II, they offer a record of how precocious the young Mendelssohn was.

Mendelssohn completed the twelfth of his thirteen string symphonies on September 17, 1823. He was 14 years old and virtually at the end of his apprentice period – even as he worked on the String Symphony No. 12, he was composing the two piano quartets that he would publish as his Opus 1. Bach was clearly the model for the String Symphony No. 12: listeners coming to this music without knowing its composer might sooner guess that it is by Bach than Mendelssohn. The slow introduction, marked Grave, is full of chromatic tension and descending lines, and at the Allegro the music leaps ahead on a fiercely-argued fugue. Relief comes in the central Andante. Young Mendelssohn divides the viola section into two parts here, giving the music a richer, fuller texture. The concluding Allegro molto is again full of sharply chromatic writing. Its vigorous introduction, which recalls material from the opening movement, gives way to a powerful fugue introduced by the second violins. A quiet interlude at the center of the movement leads to a return of the fugal writing, and Mendelssohn rounds matters off with a breathless più Allegro coda.

(Program notes by Eric Bromberger)