San Diego Symphony

Steven Schick, festival curator, conductor and performer

Rafael Payare, conductor (Haydn Symphonies No. 6-8)

Gill Sotu, spoken word poet (June 25)

MORNING: BIRDS AND LIGHT

Livestreams Friday, June 18, 2021, 7pm PDST

[program notes]

HAYDN: Symphony No. 6 in D Major, Le Matin (Morning)

MESSIAEN: Le merle noir (The Blackbird)

MISSY MAZZOLI: The Sound of Light

JOHN LUTHER ADAMS songbirdsongs (Excerpts)

Poetry by JOY HARJO and JOHN HAINES

(Read by Ariel Sanchez and Sabrina Webster)

***

NOON: THE RUSH OF WATER

Livestreams Wednesday, June 23, 7pm PDST

[program notes]

DEBUSSY: Prelude to "The Afternoon of a Faun" (arr. Sachs/Schoenberg)

GABRIELA ORTIZ: Vitrales de ambar (Stained Glasses of Amber)

TAN DUN: Water Music for Percussion Ensemble (Excerpts)

HAYDN: Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Le Midi (Noon)

Poetry by EMILY DICKINSON and MONICA SANCHEZ ESCUER

(Read by Hope-Elizabeth Dagdagan, Madeleine McCullough and Ariel Sanchez)

***

EVENING: THE EARTH RESTS

Livestreams Friday, June 25, 2021, 7pm PDST

[program notes]

OSVALDO GOLIJOV: Mariel

L. BOULANGER: D’un soir triste (Of a Sad Evening)

HAYDN: Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Le Soir (Evening)

FREDERIC RZEWSKI: To the Earth for Speaking Percussionist (Text: Homeric Hymn)

Poetry by WENDELL BERRY and GILL SOTU (world premiere; SDSO commission)

(Read by Steven Schick and performed by Gill Sotu)

***

About Our Student Poetry Readers...

- Hope-Elizabeth Dagdagan is currently a senior at the San Diego School of Creative and Performing Arts as a Musical Theater major.

- Madeleine McCullough is a sophomore at La Jolla High School and enjoys performing in her local theatre productions, going for long jogs and creative writing. She is very thankful to her music teacher and parents for allowing her to participate in this wonderful opportunity.

- Ariel Sanchez is 18 years old and recently graduated from high school after homeschooling for the past seven years. She lives in San Marcos, CA, and has been playing the piano ever since she fell in love with the instrument ten years ago.

- Sabrina Webster is a recent graduate of The Bishop’s School in La Jolla, California. In the fall, she will attend San Diego State University as a Theatre Performance major. She would like to thank the San Diego Symphony for this opportunity, her family and Leland Williams. She is grateful to be part of the San Diego Symphony’s “To The Earth” festival, and she hopes you enjoy the performance.

TO THE EARTH is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

TO THE EARTH: COMPLETE PROGRAM NOTES

MORNING: BIRDS AND LIGHT

Live-streaming Friday, June 18, 2021, 7pm

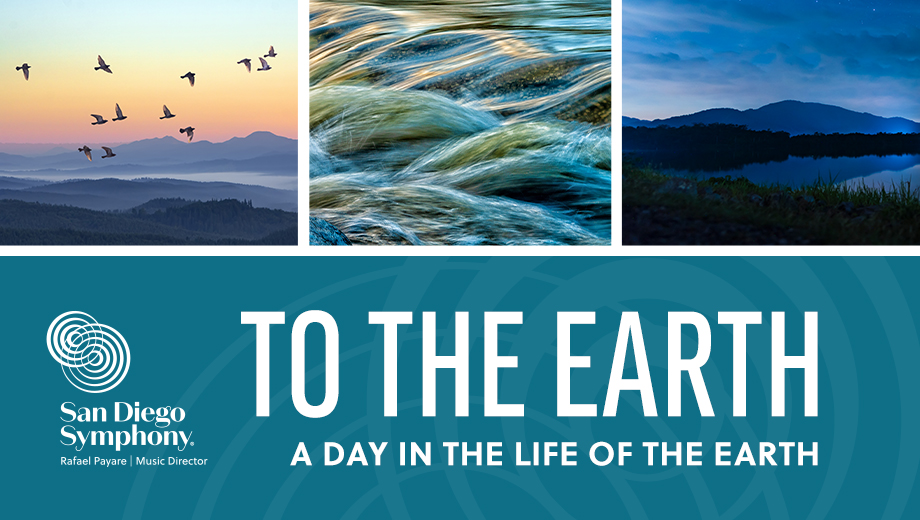

This three-concert festival series – titled “TO THE EARTH” – will explore light, water and life across the span of a single day as experienced by composer, poets and other artists. Musically, the backbone of these programs will be the triptych of symphonies that Haydn wrote as a very young man, each inspired by a different time of day: morning, noon and night. Haydn’s symphonies will be set in counterpoint to the music of nine contemporary composers who respond to the earth in quite different ways. Some hear the wondrous sound of birds around them, others see the slant of light as it appears at different times of day, and still others feel their emotions evolve and deepen as the day proceeds. It should be a lively and challenging journey as these artists make us see, hear and feel the earth in its many faces, sounds and rhythms.

We begin with the music of Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). In 1761, the 29-year-old Haydn had a request from his new patron Prince Anton for three symphonies depicting three times of day – morning, noon and night – and he quickly wrote three brief but spirited symphonies. Haydn was not particularly fond of pictorial music, and his real intention in these symphonies may have been to show off the 17-piece orchestra that he had assembled for Prince Anton’s court. These three symphonies are full of brilliant passages for solo players, and in that sense each seems more like a baroque concerto grosso than a classical symphony. In contrast to the vivid musical scene-painting of a composer like Richard Strauss, Haydn’s musical depictions can seem a little understated, but the Adagio that opens the first movement of the Symphony No. 6 is clearly a depiction of the rising sun. Across that six-measure introduction, the music begins with softly-pulsing violins, climbs upward and gathers strength, and lands on a resplendent fortissimo chord. From out of this “sunrise,” the music leaps ahead smartly at the Allegro. Longest of the movements, the Adagio – scored only for strings – offers extended solos for violin, cello and doublebass. The wind band returns for the sturdy Menuetto, while the Finale showcases the orchestra and its various principal players: solo flute leads the way, and in the course of the movement comes an extended passage of concertante writing for solo violin, as well as solos for other instruments. From the “sunrise” of the very beginning, Haydn has led us into the bright sunlight of full day.

Throughout his life, French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-92) was fascinated by the songs of birds: his mother reported that when she would push the infant Olivier in a pram, he would throw down his bottle and raise his hand to tell her to be quiet and listen to the sound of birds. As an adult, Messiaen traveled throughout the world, notating and recording different birdsongs, and he used the rhythms and motifs of those songs in his own music. Le merle noir (The Blackbird) of 1951 was his first piece to incorporate birdsong. Messiaen originally wrote Le merle noir as an examination piece for flute students at the Paris Conservatory, and like any good test-piece it is a challenge for its performers. Le merle noir has no specified meter (the barlines are present simply to indicate phrasing), and it is freely structured: Messiaen alternates florid, cadenza-like passages for the flute alone with ensemble passages that develop with the flute and piano in tight canon. The closing section, marked Vif (“Lively”) and based on the blackbird’s song, rushes Le merle noir to an animated close.

American composer Missy Mazzoli (b. 1980), who was named Composer in Residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2018, has composed three operas and much instrumental music. She has prepared an introduction to the next piece on this program: “The Sound of Light, for flute, violin, trumpet, trombone and piano, was inspired by the children I met when I visited New York Presbyterian Hospital with members of Ensemble ACJW. I was amazed at the complexity and emotional depth of the compositions these young musicians created and wanted to create a tribute to their enthusiasm and bravery. The Sound of Light is a musical depiction of growth and transformation. A lighthearted opening grows into a mysterious echoing middle section, but it’s the dancing grooves at the end that I feel best reflect the energy and spirit of all the young composers I met at the hospital.” (Missy Mazzoli)

This program concludes with excerpts from songbirdsongs by the American composer John Luther Adams (b. 1953). Adams is one of the most environmentally conscious composers today: “My music has always been profoundly influenced by the natural world and a strong sense of place. Through sustained listening to the subtle resonances of the northern soundscape, I hope to explore the territory of ‘sonic geography’ – that region between place and culture… between environment and imagination.” Adams’ Become Ocean, a warning about the future of the planet’s oceans, won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music. His songbirdsongs, composed between 1974 and 1980 and scored for three percussionists and two piccolos, spans nearly an hour; this concert will offer excerpts from it. Adams has prepared a program note for songbirdsongs, and it reads in part:

“These small songs are echoes of rare moments and places where the voices of birds have been clear and I have been quiet enough to hear. Now and then this magic finds me wandering (like one of Harry Partch’s Lost Musicians) in search of my own voice . . .

This music is not literal transcription. It is translation. Not imitation, but evocation. My concern is not with precise details of pitch and meter, for too much precision can deafen us to such things as birds and music. I listen for other, less tangible nuances. These melodies and rhythms, then, are not so much constructed artifacts as they are spontaneous affirmations.

No one has yet explained why the free songs of birds are so simply beautiful. And what do they say? What are their meanings? We may never know. But beyond the realm of ideas and emotions, language and sense, we just may hear something of their essence. From there, as Annie Dillard suggests, we can begin ‘learning the strange syllables, one by one.’” (John Luther Adams)

-Program notes by Eric Bromberger

NOON: THE RUSH OF WATER

Live-streaming Wednesday, June 23, 2021, 7pm

The second program of the “TO THE EARTH” festival takes us to mid-day. The earth has awakened, birds swirl and sing through the skies, streams tumble downhill and sunlight blazes overhead. This concert concludes with the symphony Haydn wrote specifically about noon, but we arrive at that spot only after visiting some exotic locales along the way.

We begin with one of the best-loved pieces ever written. Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” by Claude Debussy (1862-1918) may seem endlessly beautiful to us today, but it came as a shock to its first audiences. Camille Saint-Saëns was outraged by its lack of clear form and fulminated that the Prelude is “as much a piece of music as the palette a painter has worked from is a painting.”

We smile, but Saint-Saëns had a point. Though it lacks the savagery of The Rite of Spring, the Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” may be an even more revolutionary piece of music, for it does away with musical form altogether – this is not music to be grasped intellectually, but simply to be heard and felt. Pierre Boulez has said that “just as modern poetry surely took root in certain of Baudelaire’s poems, so one is justified in saying that modern music was awakened by L’après-midi d’un faune.”

Debussy based this music on the poem “L’après-midi d’un faune” by his close friend, the Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarmé. The poem is dreamlike, a series of impressions and sensations rather than a narrative. It tells of the languorous memories of a faun on a sleepy afternoon as he recalls an amorous encounter the previous day with two passing forest nymphs. This encounter may or may not have taken place, and the faun’s memories – subject to drowsiness, warm sunlight, forgetting and drink – grow vague and finally blur into sleep. Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” is heard at this concert in an arrangement for ten instruments made in 1920 by Arnold Schoenberg and his pupil Bruno Sachs.

Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz (b. 1964), the daughter of folk musicians, studied in Paris, Mexico City and London, and her music has been widely performed and acclaimed – the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and Kronos Quartet are among the many groups that have commissioned works from her. Ortiz has prepared an introduction to Vitrales de ámbar:

“The inspiration for Vitrales de ámbar (Stained Glasses of Amber) originated from two sources. The first was my request for the talented Mexican writer Monica Sanchez to write a series of small poems to describe the migration of monarch butterflies. The second has to do with a moving ABC News article published on November 20, 2008, which my dear friend Dr. Marianne Kielian-Gilbert sent me that discussed a woman’s encounter with a wounded monarch in New York State. Upon finding the wounded butterfly, she repaired its broken wing, nursed it back to health and brought it to Florida, with the help of a truck driver, in order to assist it in finishing its migration to the state of Michoacan, Mexico. The beauty of Monica’s poems and the tenderness of the article gave me countless musical ideas. In addition, the work is inspired by my memory of seeing thousands of butterflies creating a vibrant and translucent texture in the sky during a trip we made with my daughter Elena, then six years old, to Angangueo, Michoacan, to see the arrival of the monarch butterflies. In Vitrales de ámbar all these feelings and creative impulses are translated into musical prisms that intertwine and transform, creating a kind of musical kaleidoscope. The work was commissioned by Veronique Lacroix and the Ensemble Contemporain de Montréal.” (Gabriela Ortiz)

Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu, a figure universally revered for both his craftsmanship and his vision, died in 1996, and two years later Chinese composer Tan Dun (b. 1957) wrote a piece in his memory. The Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra was inspired by the sounds Tan Dun heard while growing up in Hunan Province. Water percussion refers to those sounds that can be generated in part by water, but Tan Dun turned to this particular sonority for a larger reason – for him, water is a symbol of life: “We are all linked by water,” he has said. “Life can never be without water. Water means tears. It also means the ocean.” In a published interview, the composer has suggested that the Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra raises questions like “Where did we come from?” and “Where are we going?”

The Concerto for Water Percussion and Orchestra was successfully premiered by Christopher Lamb and the New York Philharmonic in 1999 and has been frequently performed since then. From that concerto Tan Dun drew a separate work for percussion ensemble that he titled Water Music, and this concert offers excerpts from Water Music.

Our journey to mid-day concludes with the Symphony No. 7 in C Major of Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), subtitled Le midi (Noon). Certain features distinguish the Symphony No. 7 from its two companions in this symphonic triptych. First, it is in five movements rather than four. Second, the Seventh contains no musical scene-painting at all. Instead, it is full of white-hot energy – perhaps Haydn was trying to suggest the blaze of the mid-day sun here. And finally, the writing for the solo instruments is unusually brilliant in this symphony – it is as if Haydn were writing not a symphony but a concerto for orchestra. Perhaps he was giving the players in his newly-refurbished orchestra a chance to shine individually.

The first movement gets off to a powerful start with a grand slow introduction full of dotted rhythms, then goes like a rocket at the Allegro. Haydn introduces his three principal soloists here – violin I, violin II and cello – and alternates passages for full orchestra with extended passages for his three soloists. The “extra” movement in this symphony is a somber Recitativo that alternates Adagio and Allegro passages. Haydn asks for a second flute in the central Adagio, and here the silvery sound of the flute duet contrasts with vigorous passages for solo strings. There is a baroque elegance about this music, which makes its concluding moments a complete surprise: Haydn stops the orchestra and gives the first violin and cello an extended cadenza of extraordinary brilliance and difficulty. The Menuetto is quite vigorous; its trio section features the solo cello prominently. The concluding Allegro recalls the furious energy of the opening movement; the writing for the string soloists is once again brilliant, and now Haydn includes a prominent part for the solo flute.

-Program notes by Eric Bromberger

EVENING: THE EARTH RESTS

Live-streaming Friday, June 25, 2021, 7pm

The final program in the “TO THE EARTH” festival brings us to the end of day, as light fades and we slip into darkness. Night brings emotions far different from the hopes of morning or the clarity of mid-day, and the music on this concert reflects those changes.

Born in 1960 in Argentina to Jewish parents, Osvaldo Golijov had his early training in Buenos Aires, where he came to know not only classical music but also the tango as it was being reinvented by Astor Piazzolla. Golijov studied in Israel, then came to the United States, where he has since made his career. Mariel comes from a moment of personal tragedy for the composer. Mariel Stubrin, the wife of one of his closest friends, was killed in an automobile accident in southern Chile. Trying to register the emotional shock of that loss, Golijov composed Mariel in 1999, scoring it for cello and marimba. The composer has furnished a concise introduction to this music: “I wrote Mariel in memory of a friend who died in a car accident in Patagonia, where the trees are very, very tall. The inspiration there was, of course, to write an elegy for her, but I imagined the moment when grief still hadn’t arrived, the moment of being stunned by what happened, and I imagined the light of the sunshine filtering through the very tall trees. So for the marimba I imagined the refraction of the light, and the cello is like the spirit of that friend elevating. It’s almost like a painting, the idea of creating that melody and that effect of light in such a way that it’s almost like one single moment of light reverberating, rather than time progressing – suspended and vibrating, rather than going from the past to the future.”

The younger sister of the great teacher Nadia Boulanger, Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) was a musician of extraordinary talent. She was the first woman ever to win the Prix de Rome, but that promise was cut short by perpetually poor health – she was only 24 when she died, ten days before the death of Debussy. So short a life inevitably means that her output was small, and today is Lili is remembered for her vocal settings and a small amount of instrumental music. She has been described as an impressionist, but more striking are her instinctive sense of form and what is at times a surprisingly chromatic harmonic language.

In 1917, late in her brief life, Lili composed two mood-pieces, based on the same musical material but each inspired by a different time of day: the subdued D’un soir triste (“Of a Sad Evening”) and the lively D’un matin de printemps (“Of a Spring Morning”). D’un soir triste was her final composition, and she was unable to complete it. Her health was failing as she worked on it, and her manuscript – difficult to decipher – is full of corrections, crossed-out notes and sometimes superimposed notes. At the time of her death, she left D’un soir triste in three different versions: one for orchestra, another for cello and piano, and the third (the version performed at this concert) for piano trio. D’un soir triste is dark and somber: Boulanger’s “sad evening” is full of pain and sorrow. Her performance marking is Lent, grave (“slow, serious”), and the music alternates its lyric opening idea with climaxes full of stinging dissonance before the music fades into silence.

The Symphony No. 8 in G Major of Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) dates from 1761, during Haydn’s first year in the service of the musically-sophisticated Esterházy court. The Esterházy court orchestra was a good one, though in Haydn’s first years there it was small: when Haydn wrote these symphonies, it consisted of one flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns, six violins, a viola, a cello and a doublebass. Prince Anton had suggested that Haydn write a set of symphonies depicting morning, noon and evening, and the final part of this symphonic triptych, the Symphony No. 8 in G Major, has the subtitle Le Soir (The Night). Haydn was anxious to show off the individual members of his orchestra, and so he included a number of difficult solo passages for those players.

The opening Allegro molto is indeed a very fast movement: it flies along its 3/8 meter and along the way offers a number of solo passages for the flute. The graceful Andante features extended solos for the concertmaster, the principal second violin and the cello, while the sturdy Menuetto puts the spotlight on the doublebass. Up to this point, nothing in this symphony is in any way associated with the night, but now Haydn gives his finale a title, La Tempestà (The Storm), that suggests that this is a picture of a stormy night. This movement is very fast (Haydn’s marking is Presto), and once again there are prominent solo passages for the two violins and cello.

American composer Frederic Rzewski (b. 1938) studied at Harvard and Princeton with Walter Piston, Roger Sessions and Milton Babbitt before going to Italy, where he studied with Luigi Dallapiccola. A first-class pianist, Rzewski has been animated throughout his career by a commitment to social justice, a passion that has shaped much of his music. The composer has prepared a note for To the Earth:

“To the Earth was written in 1985 at the request of the percussionist Jan Williams. Williams asked for a piece using small percussion instruments that could be easily transported. I decided to use four flower pots. Not only do they have a beautiful sound but they don’t have to be carried around at all: in every place where one plays the piece, they can be bought for a total cost of about one dollar. The text, recited by the percussionist, is that of the pseudo-homeric hymn “To the Earth Mother of All,” probably written in the seventh century B.C. This simple poem is a prayer to Gaia – goddess of the Earth. The Earth is a myth, both ancient and modern. For us today as well, it appears increasingly as something fragile. Because of its humanly altered metabolism, it is rapidly becoming a symbol of the precarious human condition. In this piece the flower pots are intended to convey this sense of fragility. The writing of this piece was triggered by reading an article on newly discovered properties of clay, the substance of which pots and golems are made. Among these properties are its capacity to store energy for long periods of time and its complex molecular structure. This idea for clay as something half-alive, a kind of transitional medium between organic and inorganic materials, led me to look at flower pots. I found, in fact, that some pots are “alive” while others are “dead”: some emit a disappointing “thunk” when you tap them while others seem to burst into resonant song at the slightest touch.” (Frederic Rzewski)

-Program notes by Eric Bromberger