FEATURING THE VIOLINS, VIOLAS, CELLOS AND BASSES OF

the SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY!

"A SHIMMER OF STRINGS"

STREAMS FRIDAY, MARCH 26 @ 7PM PDT!

The silky-smooth string sections of the San Diego Symphony are highlighted in this multi-faceted program led by Music Director Rafael Payare. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's light-hearted divertimenti practically function as early short symphonies, and this program features his most popular one, in the sonorous key of B-flat Major. A marvelous gear-change brings us to the somber, brooding and gorgeous Adagio for Strings, NOT Samuel Barber's (!), but rather by one of the most acclaimed late 20th century composers in the world, Krzysztof Penderecki of Poland. Finishing out the evening's livestream is Antonín Dvoŕák's lush, melodic and sonorous Serenade for Strings, among the most famous works for strings in all of the symphonic repertoire!

San Diego Symphony Orchestra

Rafael Payare, conductor

COMPLETE PROGRAM:

MOZART: Divertimento in B-flat Major K. 137

PENDERECKI: Adagio for Strings, from Symphony No. 3

DVOŔÁK: Serenade for Strings

PROGRAM NOTES:

Divertimento in B-flat Major, K.137

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-91)

The sixteen-year-old Mozart wrote three “divertimenti” for strings (K. 136-8) in Salzburg in 1772, but a certain amount of mystery continues to surround this music. The designation “Divertimenti” in the manuscript is not in Mozart’s hand, and these three pieces lack the minuet movements characteristic of the divertimento form. Even the size of the instrumental forces Mozart had in mind is unclear: though scored for four string instruments, these works may be played by either quartet or string orchestra.

Mozart biographer Alfred Einstein suggests that these three works, composed after Mozart’s second trip to Italy, may have been written for use during his third Italian tour late in 1772 and that the simple addition of horns and oboes would transform these quartet-like works into symphonies on the three-movement Italian model. And so Mozart may have extracted double service from these three pieces: as divertimentos for string quartet in Salzburg and as potential symphonies intended for the court of Milan, where he had been feted during previous tours. The uncertainty about the form of these works has led to their being classified variously (and erroneously) as the “Salzburg symphonies” and “quartet-symphonies.”

The second of these three divertimenti, in B-flat Major, has an unusual form: the slow movement comes first, followed by two quickly-paced movements. Mozart keeps the tonality of the opening Andante uncertain throughout, constantly moving away from the home key of B-flat Major; this gives the effect of shifting patterns of color as the music moves smoothly between light and dark. After the restrained first movement, the Allegro di molto leaps out brightly. The most powerful of the three movements, it is in sonata form, though Mozart shortens the development slightly. He concludes with an elegant and poised Allegro assai in 3/8 meter, full of sharp dynamic contrasts and graceful dancing.

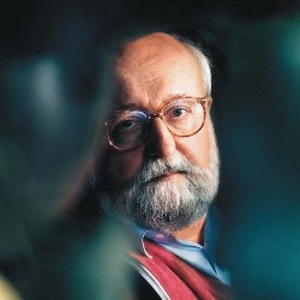

Adagio for Strings from Symphony No. 3

KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI (1933-2020)

Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki began his career as a member of the avant garde, employing fierce dissonances and incorporating such sonorities into his music as the sound of rustling paper and sawing wood: his Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 Strings (1960) established his international reputation. But in the 1970s Penderecki reversed course, writing in a more consonant harmonic language and composing in such traditional forms as symphonies (he wrote eight) and concertos. A prolific composer, he may be best remembered for his powerful liturgical works St. Luke Passion and Utrenja. He died just a year ago at age 86.

Penderecki began work on his Third Symphony in 1988, but progress was slow, and he set it aside. Penderecki actually through-composed his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies before he returned to the Third, and he finally completed it in 1995. The Third is a massive symphony – its five movements span 50 minutes – and it was successfully premiered in Munich on December 8, 1995. But Penderecki retained a special affection for its third movement, a long Adagio, and in 2013 – nearly 20 years after completing the symphony – he re-orchestrated that movement for string orchestra. Under the title Adagio for Strings, it was premiered at the Dvořák Festival in Prague in September 2013. Ironically, the Adagio for Strings has become much more famous than its parent piece, the Third Symphony, and has been recorded several times.

The Adagio for Strings is dark and grieving music. This is not program music – it tells no tale – but across its 12-minute span the Adagio sustains a most somber mood. Moments of rapt, almost luminous calm can give way to tormented climaxes. In its original form, this movement was scored largely for strings with occasional solo passages for winds, so it was not a complex task for Penderecki to reassign those solo passages to strings; there is a notable part for solo violin here. Textures remain clean, even in the most animated passages, and at the end of its dark journey the Adagio for Strings fades into troubled silence.

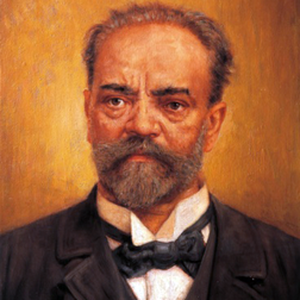

Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904)

The Serenade for Strings is a product of Dvořák’s thirty-fourth year, a time when he had just begun to devote himself to full-time composing and was achieving a wider reputation. When he wrote this Serenade in the brief span of twelve days – May 3-14, 1875 – he had not yet attained the distinctive voice that would characterize his fully mature works. Dvořák was of course anxious to have this music performed, and the score was shown to Hans Richter, newly appointed as conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic. Richter liked the work but was afraid to bring unfamiliar music before his conservative Viennese audience, and so he declined performing it. The premiere eventually took place in Prague on December 10, 1876, under Adolph Cech.

The Serenade is in five movements, and while its structure is straightforward, there are surprises along the way, moments when Dvořák can catch his audience off guard. The opening Moderato is in simple ABA form, built on a lovely, song-like first theme and a sprightly dotted second idea. The second movement is a waltz, but its trio section – which begins in such innocent loveliness – suddenly breaks off on its own and begins to develop an unexpected complexity before Dvořák takes up the waltz again. The scherzo is based on three separate theme-groups, and once again Dvořák almost has to wrench the music back to the initial scherzo theme.

The Larghetto is the emotional center of the work, a movement of serenity in the midst of the good-natured bustle of the other four. The finale, a rondo, starts off in what sounds like the wrong key – F-sharp minor – and does not settle into the home key of E Major until the second theme. As he goes along, Dvořák incorporates themes from the Larghetto and from the opening movement, and one senses a growing complexity that might be out of place in a serenade except that Dvořák does it with such grace and ease that he disarms all criticism. The music reaches a quiet pause and then makes a sudden rush to the end of what is one of Dvořák’s friendliest scores.

-Program notes by Eric Bromberger