ENIGMA VARIATIONS, OP. 36

Who are the personalities behind Elgar's intriguing Enigma Variations?

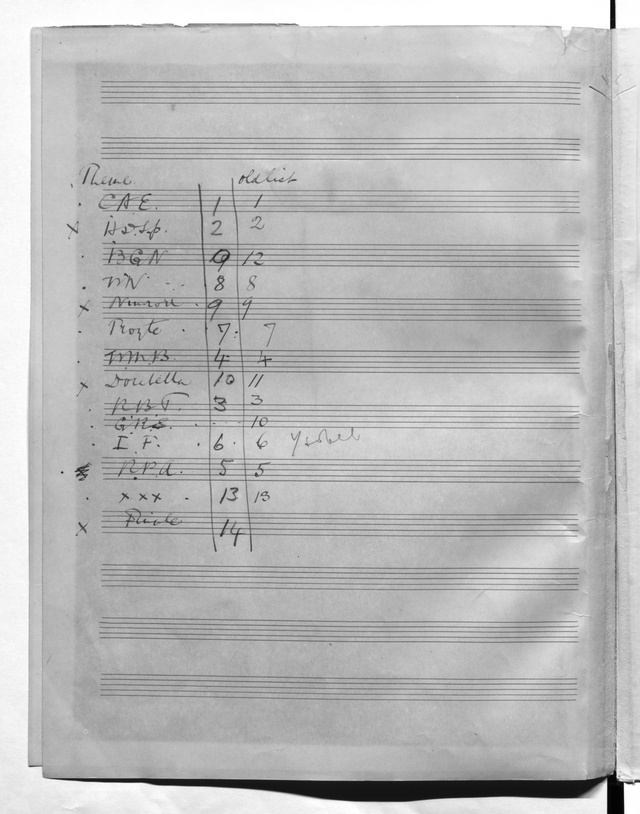

For full descriptions of Elgar's “friends pictured within,” we are indebted to the invention of the piano roll; when the Aeolian Company later issued the Enigma Variations in this newfangled format, Elgar contributed his own comments on this circle of men and women in his life. Here, then, follows the portrait gallery, with some of Elgar’s remarks.

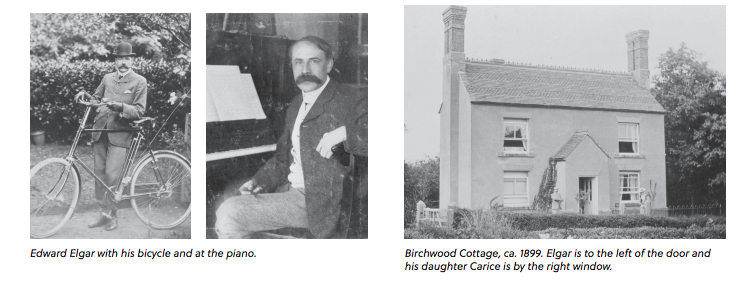

Theme. This is an original melody, as Elgar’s title boasts, born that October night in 1898 and without connections to anyone in the composer’s life. (It has been suggested that those important first four notes perfectly set the composer’s own name, but, as we shall see, Elgar saves himself for last.) It’s worth remembering, however, that when he wrote The Music Makers (an autobiographical, Ein Heldenleben–kind of work) in 1912, he recalled this theme to represent the loneliness of the creative artist.

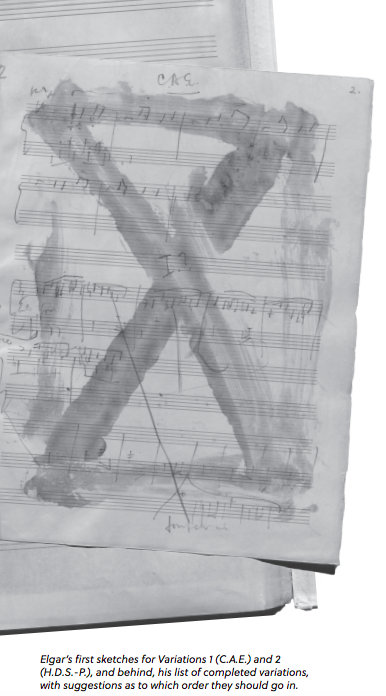

(C.A.E.) Caroline Alice Elgar was the composer’s wife. “The variation,” Elgar writes, “is really a prolongation of the theme with what I wished to be romantic and delicate additions; those who knew C.A.E. will understand this reference to one whose life was a romantic and delicate inspiration.” She was his muse; after Alice died in 1920, Elgar never really worked again. The little triplet figure in the oboe and the bassoon at the very beginning mimics the whistle with which Elgar signaled Alice whenever he came home.

1. (H.D.S.-P.) Hew David Steuart-Powell played chamber music with Elgar. “His characteristic diatonic run over the keys before beginning to play is here humorously travestied in the semiquaver [sixteenth note] passages; these should suggest a toccata, but chromatic beyond H.D.S.-P.’s liking.” (Their frequent partner was Basil Nevinson - Variation 12.)

2. (R.B.T.) Richard Baxter Townshend, who regularly rode through the streets of Oxford on his bicycle with the bell constantly ringing, is here remembered for his “presentation of an old man in some amateur theatricals—the low voice flying off occasionally in ‘soprano’ timbre.” (Dorabella also recognized the bicycle bell in the pizzicato strings.

3. (W.M.B.) William Meath Baker was “a country squire, gentleman, and scholar. In the days of horses and carriages, it was more difficult than in these days of petrol to arrange the carriages for the day to suit a large number of guests. This variation was written after the host had, with a slip of paper in his hand, forcibly read out the arrangements for the day and hurriedly left the music room with an inadvertent bang of the door.”

4. (R.P.A.) Richard Penrose Arnold was a son of Matthew Arnold and “a great lover of music which he played (on the pianoforte) in a self-taught manner, evading difficulties but suggesting in a mysterious way the real feeling.” In the middle section we learn that “his serious conversation was continually broken up by whimsical and witty remarks.”

5. (Ysobel) Isabel Fitton was an amateur violist. “The opening bar, a phrase made use of throughout the variation, is an ‘exercise’ for crossing strings—a difficulty for beginners; on this is built a pensive, and for a moment, romantic movement.”

6. (Troyte) Arthur Troyte Griffith, an architect, was one of Elgar’s closest friends. “The uncouth rhythm of the drums and lower strings was really suggested by some maladroit essays to play the pianoforte; later the strong rhythm suggests the attempts of the instructor (E.E.) to make something like order out of chaos, and the final despairing ‘slam’ records that the effort proved to be in vain.”

7. (W.N.) Winifred Norbury lived at Sherridge, a country house, with her sister Florence. The music was “really suggested by an eighteenth-century house. The gracious personalities of the ladies are sedately shown”—especially Winifred’s characteristic laugh.

8. (Nimrod) Nimrod is the “mighty hunter” named in Genesis 10; August Jaeger (“Jaeger” is German for “hunter”) was Elgar’s greatest and dearest friend. That is apparent from this extraordinary music, which is about the strength of ties and the depth of human feelings. These forty-three bars of music have come to mean a great deal to many people; they are, for that reason, often played in memoriam, when common words fail and virtually all other music falls short. The variation records “a long summer evening talk, when my friend discoursed eloquently on the slow movements of Beethoven.” The music hints at the slow movement of the Pathétique Sonata, though it reaches the more rarefied heights of Beethoven’s last works. Dorabella remembered that Jaeger also spoke of the hardships Beethoven endured, and he urged Elgar not to give up. Elgar later wrote to him: “I have omitted your outside manner and have only seen the good lovable honest SOUL in the middle of you. The music’s not good enough: nevertheless it was an attempt of your E.E.” Jaeger died young, in 1909. Twenty years later Elgar wrote: “His place has been occupied but never filled.”

9. (Dorabella) Dora Penny, later Mrs. Richard Powell, and to the Elgars, always Dorabella, from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Her variation, entitled Intermezzo, is shaded throughout by “a dancelike lightness,” and delicately suggests the stammer with which she spoke in her youth.

10. (G.R.S.) Dr. George R. Sinclair was the organist of Hereford Cathedral, though it’s his beloved bulldog Dan who carries the music, first falling down a steep bank into the River Wye, then paddling upstream to a safe landing. Anticipating the skeptics, Elgar writes “Dan” in bar five of the manuscript, where Dr. Sinclair’s dog barks reassuringly (low strings and winds, fortissimo).

11. (B.G.N.) Basil G. Nevinson was a fine cellist who regularly joined Elgar and Hew David Steuart-Powell (Variation 2) in chamber music. The soaring cello melody is “a tribute to a very dear friend whose scientific and artistic attainments, and the whole-hearted way they were put at the disposal of his friends, particularly endeared him to the writer.”

12. (***) The only true enigma among the portraits: just asterisks in place of initials, and “Romanza” at the top of the page. The clarinet quoting from Mendelssohn’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage midway through points to Lady Mary Lygon, who supposedly was crossing the sea to Australia as Elgar wrote this music (she wasn’t). “The drums suggest the distant throb of a liner,” Elgar writes. Although Elgar eventually confirmed the attribution, it has never entirely satisfied a suspicious public. Dorabella claimed that in the composer’s mind, the asterisks stood for “My sweet Mary.”

13. (E.D.U.) Edu was Alice’s nickname for her husband. This is his self-portrait, written “at a time when friends were dubious and generally discouraging as to the composer’s musical future.” Alice and Jaeger, two who never lost their faith in him, make brief appearances. The music is forceful, even bold. It’s delivered with an unusual strength known best to late bloomers, the defiance of an outsider intent on finding an audience, and the confidence of a man who has always wished to be more than another variation on a theme.

Notes by Phillip Huscher, program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Richard Rodda, who provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals. Reprinted and modified with permission. © 2019 by CSOA

Share Article

Back to all posts